Price: 136.84 - 74.41

Journalism faces a credibility crisis. Only 32% of Americans report having “a great deal” or “fair amount” of trust in news reporting—a historical low.

Journalists generally assume that their lack of credibility is a result of what people believe to be reporters’ and editors’ political bias. So they believe the key to improving public trust is to banish any traces of political bias from their reporting.

That explains why newsroom leaders routinely advocate for maintaining “objectivity” as a journalistic value and admonish journalists for sharing their own opinions on social media.

The underlying assumption is straightforward: News organizations are struggling to maintain public trust because journalists keep giving people reasons to distrust the people who bring them the news. Newsroom managers appear to believe that if the public perceives their journalists as politically neutral, objectively minded reporters, they will be more likely to trust—and perhaps even pay for—the journalism they produce.

Yet, a study I recently published with journalism scholars Seth Lewis and Brent Cowley in Journalism, a scholarly publication, suggests this path of distrust stems from an entirely different problem.

Drawing on 34 Zoom-based interviews with adults representing a cross-section of age, political leaning, socioeconomic status and gender, we found that people’s distrust of journalism does not stem from fears of ideological brainwashing. Instead, it stems from assumptions that the news industry as a whole values profits above truth or public service.

The Americans we interviewed believe that news organizations report the news inaccurately not because they want to persuade their audiences to support specific political ideologies, candidates or causes, but rather because they simply want to generate larger audiences—and therefore larger profits.

The business of journalism depends primarily on audience attention. News organizations make money from this attention indirectly, by profiting off the advertisements—historically print and broadcast, now increasingly digital—that accompany news stories. They also monetize this attention directly, by charging audiences for subscriptions to their offerings.

Many news organizations pursue revenue models that combine both of these approaches, despite serious concerns about the likelihood of either leading to financial stability.

Although news organizations depend on revenue to survive, journalism as a profession has long maintained a “firewall” between its editorial decisions and business interests. One of journalism’s long-standing values is that journalists should cover whatever they want without worrying about the financial implications for their news organization. NPR’s Ethics Handbook, for example, states that “the purpose of our firewall is to hold in check the influence our funders have over our journalism.”

What does this look like in practice? It means that journalists at the Washington Post should, according to these principles, feel encouraged to pursue investigative reporting into Amazon despite the fact that the newspaper is owned by Amazon founder and executive chairman Jeff Bezos.

While the effectiveness of this firewall in the real world is far from assured, its existence as a principle within the profession suggests that many working journalists pride themselves on following the story wherever it leads, regardless of its financial ramifications for their organization.

Yet despite the importance of this principle to journalists, the people we interviewed seemed unaware of its importance—indeed, its very existence.

The people we spoke with tended to assume that news organizations made money primarily through advertising instead of also from subscribers. That led many to believe that news organizations are pressured to pursue large audiences so that they can generate more advertising revenue.

Consequently, many of the people interviewed described journalists as being enlisted in an ongoing, never-ending struggle to capture public attention in an incredibly crowded media environment.

“If you don’t get a certain number of views, you’re not making enough money,” said one of our interviewees, “and then that doesn’t end well for the company.”

People we spoke with tended to agree that journalism is biased, and assumed that such bias exists for profit-oriented rather than strictly ideologically oriented reasons. Some see a convergence in these reasons.

“[Journalists] get money from various support groups that want to see a particular agenda pushed, like George Soros,” said another interviewee. “It’s profits over journalism and over truth.”

Others we spoke with understood that some news organizations depend primarily on their audiences for financial support in the form of subscriptions, donations or memberships. Although these interviewees saw news organizations’ means of generating revenue differently from those who assumed that the money mostly came from advertising, they still described deep distrust toward the news that stemmed from concerns about the news industry’s commercial interests.

“That’s how they make money,” one person said about subscriptions. “They want to entice you with a different version of the news that is not, I personally believe, overall going to be accurate. They get you to pay for that and—poof—you’re a sucker.”

In light of these findings, it appears that journalists’ concerns that they must defend themselves against accusations of ideological bias might be misplaced.

Many news organizations have pursued efforts at transparency as an overarching approach to earning public trust, with the implicit goal being to demonstrate that they are doing their work with integrity and free from any ideological bias.

Since 2020, for example, The New York Times has maintained a “Behind the Journalism” page that describes how the newspaper’s reporters and editors approach everything, from when they use anonymous sources to how they confirm breaking crime news and how they are covering the Israel-Hamas War. The Washington Post similarly began maintaining a “Behind the Story” page in 2022.

Yet these displays do not address the chief cause for concern among the people we interviewed: the influence of profit-chasing on journalistic work.

Instead of worrying quite so much about perceptions of journalists’ political biases, it might be more beneficial for newsroom managers to shift their energies to pushing back against perceptions of economic bias.

Perhaps a more effective demonstration of transparency would focus less on how journalists do their jobs and more on how news organizations’ financial concerns are kept separate from evaluations of journalists’ work.

The people we interviewed also often appeared to conflate television news with other forms of news production, such as print, digital and radio. And there is ample evidence that television news managers do indeed appear to privilege profits over journalistic integrity.

“It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS,” said CBS chairman Leslie Moonves of the massive coverage of then-presidential candidate Donald Trump in 2016. “The money’s rolling in.”

With that in mind, perhaps discussions about improving trust in journalism could begin by acknowledging the extent to which the public’s skepticism toward the media is well-founded—or, at the very least, by more explicitly distinguishing between different kinds of news production.

In short, people are skeptical of the news and distrustful of journalists, not because they think journalists want to brainwash them into voting certain ways, but because they think journalists want to make money off their attention above all else.

For journalists to seriously address the root causes of the public’s distrust in their work, they will need to acknowledge the economic nature of that distrust and reckon with their role in its perpetuation.

Provided by

The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Citation:

Journalism’s trust problem is about money, not politics (2024, June 26)

retrieved 26 June 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-06-journalism-problem-money-politics.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

Google co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin loved pulling pranks, so much so they began rolling outlandish ideas every April Fool’s Day not long after starting their company more than a quarter century ago. One year, Google posted a job opening for a Copernicus research center on the moon. Another year, the company said it planned to roll out a “scratch and sniff” feature on its search engine.

The jokes were so consistently over-the-top that people learned to laugh them off as another example of Google mischief. And that’s why Page and Brin decided to unveil something no one would believe was possible 20 years ago on April Fool’s Day.

It was Gmail, a free service boasting 1 gigabyte of storage per account, an amount that sounds almost pedestrian in an age of one-terabyte iPhones. But it sounded like a preposterous amount of email capacity back then, enough to store about 13,500 emails before running out of space compared to just 30 to 60 emails in the then-leading webmail services run by Yahoo and Microsoft. That translated into 250 to 500 times more email storage space.

Besides the quantum leap in storage, Gmail also came equipped with Google’s search technology so users could quickly retrieve a tidbit from an old email, photo or other personal information stored on the service. It also automatically threaded together a string of communications about the same topic so everything flowed together as if it was a single conversation.

“The original pitch we put together was all about the three ‘S’s”—storage, search and speed,” said former Google executive Marissa Mayer, who helped design Gmail and other company products before later becoming Yahoo’s CEO.

It was such a mind-bending concept that shortly after The Associated Press published a story about Gmail late on the afternoon of April Fool’s 2004, readers began calling and emailing to inform the news agency it had been duped by Google’s pranksters.

“That was part of the charm, making a product that people won’t believe is real. It kind of changed people’s perceptions about the kinds of applications that were possible within a web browser,” former Google engineer Paul Buchheit recalled during a recent AP interview about his efforts to build Gmail.

It took three years to do as part of a project called “Caribou”—a reference to a running gag in the Dilbert comic strip. “There was something sort of absurd about the name Caribou, it just made make me laugh,” said Buchheit, the 23rd employee hired at a company that now employs more than 180,000 people.

The AP knew Google wasn’t joking about Gmail because an AP reporter had been abruptly asked to come down from San Francisco to the company’s Mountain View, California, headquarters to see something that would make the trip worthwhile.

After arriving at a still-developing corporate campus that would soon blossom into what became known as the “Googleplex,” the AP reporter was ushered into a small office where Page was wearing an impish grin while sitting in front of his laptop computer.

Page, then just 31 years old, proceeded to show off Gmail’s sleekly designed inbox and demonstrated how quickly it operated within Microsoft’s now-retired Explorer web browser. And he pointed out there was no delete button featured in the main control window because it wouldn’t be necessary, given Gmail had so much storage and could be so easily searched. “I think people are really going to like this,” Page predicted.

As with so many other things, Page was right. Gmail now has an estimated 1.8 billion active accounts—each one now offering 15 gigabytes of free storage bundled with Google Photos and Google Drive. Even though that’s 15 times more storage than Gmail initially offered, it’s still not enough for many users who rarely see the need to purge their accounts, just as Google hoped.

The digital hoarding of email, photos and other content is why Google, Apple and other companies now make money from selling additional storage capacity in their data centers. (In Google’s case, it charges anywhere from $30 annually for 200 gigabytes of storage to $250 annually for 5 terabytes of storage). Gmail’s existence is also why other free email services and the internal email accounts that employees use on their jobs offer far more storage than was fathomed 20 years ago.

“We were trying to shift the way people had been thinking because people were working in this model of storage scarcity for so long that deleting became a default action,” Buchheit said.

Gmail was a game changer in several other ways while becoming the first building block in the expansion of Google’s internet empire beyond its still-dominant search engine.

After Gmail came Google Maps and Google Docs with word processing and spreadsheet applications. Then came the acquisition of video site YouTube, followed by the introduction of the the Chrome browser and the Android operating system that powers most of the world’s smartphones. With Gmail’s explicitly stated intention to scan the content of emails to get a better understanding of users’ interests, Google also left little doubt that digital surveillance in pursuit of selling more ads would be part of its expanding ambitions.

Although it immediately generated a buzz, Gmail started out with a limited scope because Google initially only had enough computing capacity to support a small audience of users.

“When we launched, we only had 300 machines and they were really old machines that no one else wanted,” Buchheit said, with a chuckle. “We only had enough capacity for 10,000 users, which is a little absurd.”

But that scarcity created an air of exclusivity around Gmail that drove feverish demand for an elusive invitations to sign up. At one point, invitations to open a Gmail account were selling for $250 apiece on eBay. “It became a bit like a social currency, where people would go, ‘Hey, I got a Gmail invite, you want one?'” Buchheit said.

Although signing up for Gmail became increasingly easier as more of Google’s network of massive data centers came online, the company didn’t begin accepting all comers to the email service until it opened the floodgates as a Valentine’s Day present to the world in 2007.

A few weeks later on April Fool’s Day in 2007, Google would announce a new feature called “Gmail Paper” offering users the chance to have Google print out their email archive on “94% post-consumer organic soybean sputum ” and then have it sent to them through the Postal Service. Google really was joking around that time.

© 2024 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.

Citation:

Gmail revolutionized email 20 years ago. People thought it was Google’s April Fool’s Day joke (2024, March 31)

retrieved 26 June 2024

from https://techxplore.com/news/2024-03-gmail-revolutionized-email-years-people.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

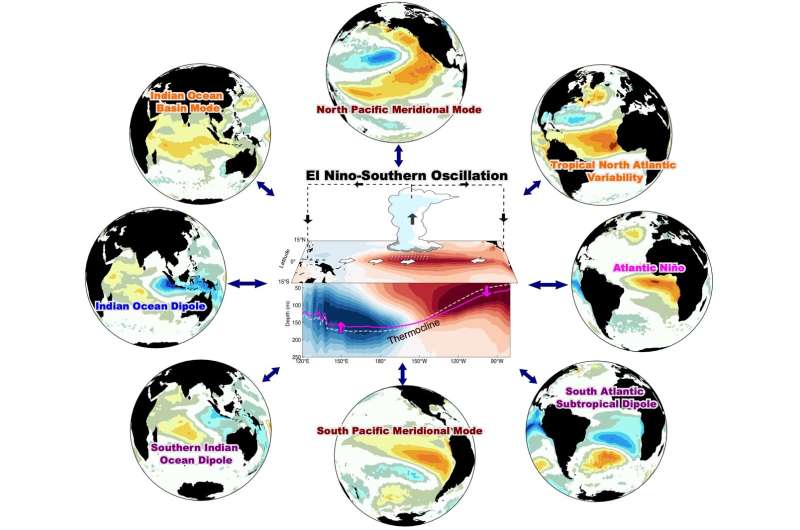

Across Asia, the Pacific Ocean, and the Americas, El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) brings variations in winds, weather, and ocean temperature that can cause droughts, floods, crop failures, and food shortages. Recently, the world has experienced a major El Niño event in 2023–2024, dramatically impacting weather, climate, ecosystems, and economies globally.

By developing an innovative modeling approach, researchers from the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST) at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa are now able to forecast ENSO events up to 18 months ahead of time—significantly improving conventional climate model forecasting.

Their findings, which meld insights into the physics of the ocean and atmosphere with predictive accuracy, were published in Nature.

“We have developed a new conceptual model—the so-called extended nonlinear recharge oscillator (XRO) model—that significantly improves predictive skill of ENSO events at over one year in advance, better than global climate models and comparable to the most skillful AI forecasts,” said Sen Zhao, lead author of the study and an assistant researcher in SOEST.

“Our model effectively incorporates the fundamental physics of ENSO and ENSO’s interactions with other climate patterns in the global oceans that vary from season to season.”

Scientists have been working for decades to improve ENSO predictions given its global environmental and socioeconomic impacts. Traditional operational forecasting models have struggled to successfully predict ENSO with lead times exceeding one year.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have pushed these boundaries, achieving accurate predictions up to 16–18 months in advance. However, the “black box” nature of AI models has precluded attribution of this accuracy to specific physical processes.

Not being able to explain the source of the predictability in the AI models results in low confidence that these predictions will be successful for future events as the Earth continues to warm, changing the currents in the oceans and atmosphere.

“Unlike the ‘black box’ nature of AI models, our XRO model offers a transparent view into the mechanisms of the equatorial Pacific recharge-discharge physics and its interactions with other climate patterns outside of tropical Pacific,” explained Fei-Fei Jin, the corresponding author and professor of atmospheric sciences in SOEST.

“The initial states of the extratropical Pacific, tropical Indian Ocean, and Atlantic enhance ENSO predictability in distinct seasons. For the first time, we are able to robustly quantify their impact on ENSO predictability, thus deepening our knowledge of ENSO physics and its sources of predictability.”

“Our findings also identify shortcomings in the latest generation of climate models that lead to their failure in predicting ENSO accurately,” said Malte Stuecker, assistant professor of oceanography in SOEST and study co-author.

“To improve ENSO predictions, climate models must correctly capture the key physics of ENSO and additionally, three compounding aspects of other climate patterns in the global oceans: accurate knowledge of the state of each of these climate patterns when the ENSO forecasts starts, the correct seasonally varying ‘ocean memory’ of each of these climate patterns, and correct representations of how each of these other climate patterns affect ENSO in different seasons.”

“Different sources of predictability lead to distinct ENSO event evolutions,” said Philip Thompson, associate professor of oceanography in SOEST and co-author of the study. “We are now able to provide skillful, long lead time predictions of this ‘ENSO diversity,’ which is critical as different flavors of ENSO have very different impacts on global climate and individual communities.”

“In addition to El Niño, the new XRO model also improves predictability of other climate variabilities in tropical Indian and Atlantic Oceans, such as the Indian Ocean Dipole, which can significantly alter the local and global weather patterns beyond the impacts of El Niño,” added Zhao.

The implications of this research are far-reaching, offering prospects for more accurate and longer lead time ENSO predictions and global climate model improvements.

Though ENSO originates in the tropical Pacific, we can no longer think of it as a tropical Pacific Ocean problem only, either from a modeling and prediction perspective or from an observational perspective. The global tropics and the higher latitudes are integral to improving seasonal climate forecasts.

“By tracing model shortcomings and understanding these climate pattern interactions with our new conceptual XRO model, we can substantially refine our global climate models,” remarked Stuecker.

“This paves the way for the next-generation of global climate models to incorporate these findings, improving our approach to predicting and mitigating the effects of climate variability and change. Such advancements are crucial for societal preparations and adaptations to climate-related hazards.”

The UH team of researchers was rounded out with contributing authors from Columbia University, NOAA, Korea, and China.

More information:

Fei-Fei Jin, Explainable El Niño predictability from climate mode interactions, Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07534-6. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07534-6

Provided by

University of Hawaii at Manoa

Citation:

El Niño forecasts extended to 18 months with physics-based model (2024, June 26)

retrieved 26 June 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-06-el-nio-months-physics-based.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

In a rare opportunity to study carnivores before and after wolves were reintroduced to their ranges, researchers from the University of Wisconsin–Madison found that the effects of wolves on Isle Royale have been only temporary. And even in the least-visited national park, humans had a more significant impact on carnivores’ lives.

The paper, published recently in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, uses DNA from foxes and martens’ scat and hair to understand where these animals were and what they ate before wolves were reintroduced, following the first year of their reintroduction, and as they formed packs across the island.

While many studies have been conducted to understand the effects of a carnivore reintroduction on their prey, less well studied is the effect of the reintroduction on other carnivores in the same food web, in this case foxes and martens.

“We had this really amazing opportunity in Isle Royale—where we had data before this large carnivore reintroduction and then following the reintroduction of wolves—where we could look at how these effects within carnivores are taking place, and how they shift,” says Mauriel Rodriguez Curras, who completed this work as a graduate student in the lab of UW–Madison forest and wildlife ecology professor Jonathan Pauli.

Isle Royale is a remote island in Lake Superior and its isolated geography and limited variety of animals—including moose, beavers and squirrels—make the island a relatively simple ecosystem in which to study the complexities of carnivore reintroductions.

Wolves first came to Isle Royale in the 1940s, likely by means of an ice bridge that formed naturally across 15 miles of Lake Superior from Minnesota or Canada to the island. Recently, climate change has kept ice bridges from forming as often, meaning new wolves can’t cross over to Isle Royale.

While the island once had 50 wolves across several packs, by 2018 there were just two wolves left: a father daughter duo that, due to inbreeding, were also half siblings. With the goal of restoring the natural apex predator to the island and rebalancing the ecosystem, 19 wolves were introduced by the park to Isle Royale in 2019.

For this study, a typical field day involved hiking between 15 and 20 miles of trail to check traps—open PVC tubes with little brushes inside them—for hair samples and looking for scat to swab and collect. Once back at UW–Madison, Rodriguez Curras and Pauli extracted DNA from both the samples and determined which individual fox or marten it was from. By measuring ratios of carbon and nitrogen present in the samples, they could also reconstruct the animals’ diets.

From their analysis, Rodriguez Curras and Pauli categorized the effects from wolves on other carnivores into three phases: absence, establishment and coalescence. The absence phase is data the lab had collected on foxes and martens the year before wolves were reintroduced to the island.

During establishment, which included the first year of the wolves’ reintroduction, no clear territories or packs had established, and the wolves were wandering the island mostly as individuals. Foxes altered where they hung out on the island in this phase, moving away from the dense forest and closer to campgrounds.

Since foxes compete with martens for food and have been known to kill them, martens normally stick to the densely forested areas of the island where it’s easier to hide. But, with foxes shifting to other areas of the island after wolf reintroduction, martens were able to expand their distribution on the island and increase their population.

Meanwhile, foxes found themselves facing greater risk. Foxes hunt small prey, but they often rely on scavenging. Theoretically, scavenging off wolf kills is beneficial to the foxes who couldn’t easily kill prey as large as a beaver or a moose calf. But to scavenge off those kills they would also have to be in areas the wolves are regularly, elevating the risk of being killed. So, rather than contend with wolves all the time, foxes supplemented their food by sticking close to campgrounds. They leveraged their cuteness and begging and raiding skills to target an easier meal: food from human visitors.

By 2020, the wolves had coalesced into packs with defined territories. The effects of wolves on the other carnivores disappeared, and foxes and martens occupied areas and ate food similar to the absence phase.

“The rewilding of these species is an important move that conservation biologists are making to try and reweave the fabric of ecosystem function,” said Pauli who’s been studying the island for 8 years. “But I think the point is that when we do this reweaving of communities, unexpected things happen. I don’t think these are bad things, but they’re not necessarily things that we’d immediately predict.”

Another unexpected consequence was how strongly human visitors to the island could affect these species interactions. Even though Isle Royale is considered one of the most pristine wilderness areas in the country and is one of the least-visited national park, Rodriguez Curras and Pauli found that humans, and the food they bring with them, have a significant effect on the relationship between the carnivores, where they live, what they eat and how they then interact.

Rodriguez Curras and Pauli credit their partnership with the National Park Service for providing the opportunity to conduct research that can guide ongoing and future carnivore reintroduction efforts in other areas. Their work revealing the way species interact with one another and with humans also provides Isle Royale National Park with the best available science to potentially improve visitors’ experiences while preserving the island’s wilderness.

More information:

Mauriel Rodriguez Curras et al, The pulsed effects of reintroducing wolves on the carnivore community of Isle Royale, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (2024). DOI: 10.1002/fee.2750

Provided by

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Citation:

Wolves reintroduced to Isle Royale temporarily affect other carnivores, humans have influence as well (2024, June 26)

retrieved 26 June 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-06-wolves-reintroduced-isle-royale-temporarily.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.