A new peer-reviewed study from researchers at The University of Texas at Arlington; the University of Nevada, Reno; Mokwon University in Daejeon, Korea; and Texas A&M University at Corpus Christi shows the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill of 2010 affected wildlife and their habitat much more than previously understood.

The work is published in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin.

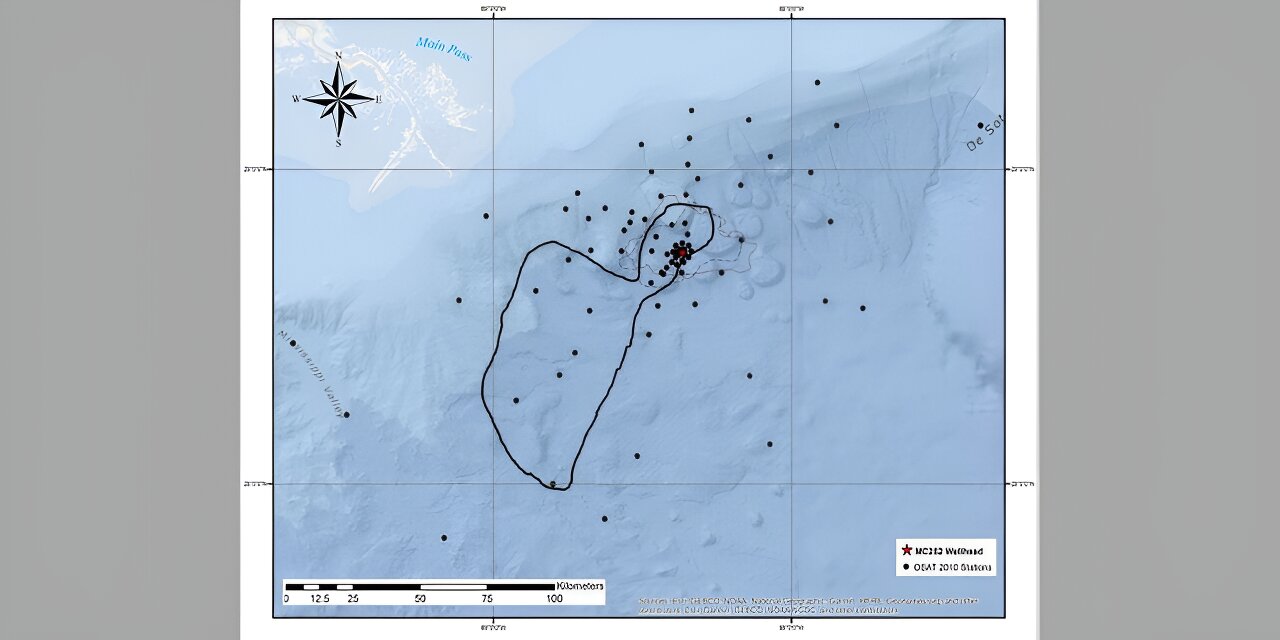

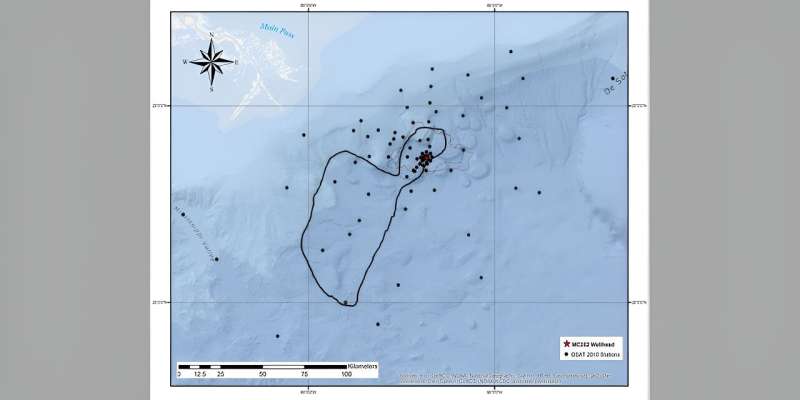

“Overall, we found the area of deep-sea floor affected by the DWH spill was significantly larger than previously thought,” said Masoud Rostami, an author of the study and assistant professor of instruction in UTA’s Division of Data Science.

In recent decades, deep-water ecosystems in lakes, oceans, and seas around the world have faced pressures from offshore oil and gas production, including frequent contamination from oil and other pollutants. The DWH oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico that started on April 20, 2010, was the largest marine oil spill in U.S. history, releasing nearly 5 million barrels of crude oil and hydrocarbon gases over 87 days, with 3.2 million barrels of oil remaining in the water after cleanup efforts.

This spill greatly exceeded the amount of natural discharge of oil that seeps in the Gulf each year, and up to 35% of the pollutants were trapped below the surface, severely impacting the lives and habitats of the plants, animals, and microorganisms (like bacteria and fungi) that live deep in the ocean. For this study, the researchers focused on the harpacticoid copepods, a type of crustacean that lives near the bottom of the ocean, to better understand the DWH spill’s effects on the deep-sea ecosystem in the Gulf of Mexico. Copepods are good for this type of study because they live in several different deep-sea habitats and are known to be sensitive to pollution.

Researchers found that the spill affected biodiversity over an area of 1,100 square miles—a area nearly nine times larger than earlier studies on DWH. Using advanced methodologies, including remote sensing, multivariate statistical analysis, and machine-learning approaches, the team detected subtle changes in the deep-sea copepod community composition.

“This study demonstrates that harpacticoid copepod diversity dramatically declined because of DWH oil pollution,” said Rostami.

More information:

Jeffrey G. Baguley et al, Harpacticoid copepods expand the scope and provide family-level indicators of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill deep-sea impacts, Marine Pollution Bulletin (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.116343

Provided by

University of Texas at Arlington

Citation:

Biodiversity loss from 2010 oil spill worse than predicted (2024, June 24)

retrieved 25 June 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-06-biodiversity-loss-oil-worse.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.