MIT physicists and colleagues report new insights into exotic particles key to a form of magnetism that has attracted growing interest because it originates from ultrathin materials only a few atomic layers thick. The work, which could impact future electronics and more, also establishes a new way to study these particles through a powerful instrument at the National Synchrotron Light Source II at Brookhaven National Laboratory.

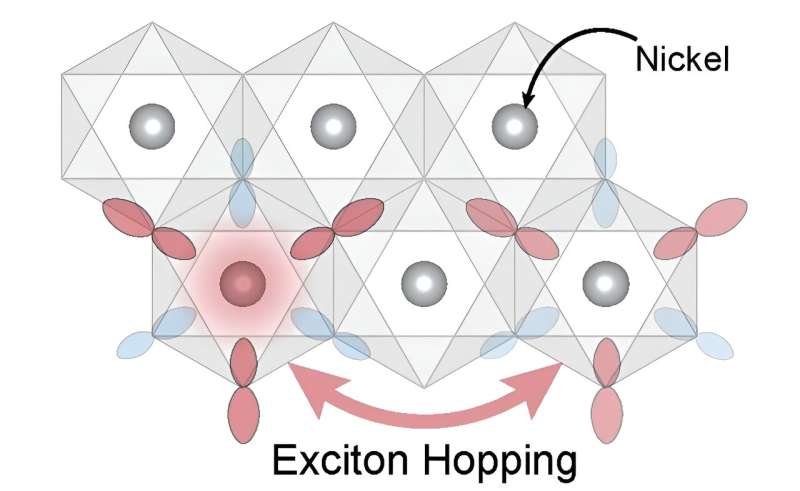

Among their discoveries, the team has identified the microscopic origin of these particles, known as excitons. They showed how they can be controlled by chemically “tuning” the material, which is primarily composed of nickel. Further, they found that the excitons propagate throughout the bulk material instead of being bound to the nickel atoms.

Finally, they proved that the mechanism behind these discoveries is ubiquitous to similar nickel-based materials, opening the door for identifying—and controlling—new materials with special electronic and magnetic properties.

The open-access results are reported in the July 12 issue of Physical Review X.

“We’ve essentially developed a new research direction into the study of these magnetic two-dimensional materials that very much relies on an advanced spectroscopic method, resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS), which is available at Brookhaven National Lab,” says Riccardo Comin, MIT’s Class of 1947 Career Development Associate Professor of Physics and leader of the work.

Ultrathin layers

The magnetic materials at the heart of the current work are known as nickel dihalides. They are composed of layers of nickel atoms sandwiched between layers of halogen atoms (halogens are one family of elements), which can be isolated to atomically thin layers. In this case, the physicists studied the electronic properties of three different materials composed of nickel and the halogens chlorine, bromine, or iodine. Despite their deceptively simple structure, these materials host a rich variety of magnetic phenomena.

The team was interested in how these materials’ magnetic properties respond when exposed to light. They were specifically interested in particular particles—the excitons—and how they are related to the underlying magnetism. How exactly do they form? Can they be controlled?

Enter excitons

A solid material is composed of different types of elementary particles, such as protons and electrons. Also ubiquitous in such materials are “quasiparticles” that the public is less familiar with. These include excitons, which are composed of an electron and a “hole,” or the space left behind when light is shone on a material and energy from a photon causes an electron to jump out of its usual position.

Through the mysteries of quantum mechanics, however, the electron and hole are still connected and can “communicate” with each other through electrostatic interactions. This interaction leads to a new composite particle formed by the electron and the hole—an exciton.

Excitons, unlike electrons, have no charge but possess spin. The spin can be thought of as an elementary magnet, in which the electrons are like little needles orienting in a certain way. In a common refrigerator magnet, the spins all point in the same direction. Generally speaking, the spins can organize in other patterns leading to different kinds of magnets. The unique magnetism associated with the nickel dihalides is one of these less-conventional forms, making it appealing for fundamental and applied research.

The MIT team explored how excitons form in the nickel dihalides. More specifically, they identified the exact energies, or wavelengths, of light necessary for creating them in the three materials they studied.

“We were able to measure and identify the energy necessary to form the excitons in three different nickel halides by chemically ‘tuning,’ or changing, the halide atom from chlorine to bromine to iodine,” says Occhialini. “This is one essential step towards understanding how photons—light—could one day be used to interact with or monitor the magnetic state of these materials.” Ultimate applications include quantum computing and novel sensors.

The work could also help predict new materials involving excitons that might have other interesting properties. Further, while the studied excitons originate on the nickel atoms, the team found that they do not remain localized to these atomic sites. Instead, “we showed that they can effectively hop between sites throughout the crystal,” Occhialini says. “This observation of hopping is the first for these types of excitons, and provides a window into understanding their interplay with the material’s magnetic properties.”

A special instrument

Key to this work—in particular for observing the exciton hopping—is resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS), an experimental technique that co-authors Pelliciari and Bisogni helped pioneer. Only a few facilities in the world have advanced high energy resolution RIXS instruments. One is at Brookhaven. Pelliciari and Bisogni are part of the team running the RIXS facility at Brookhaven. Occhialini will be joining the team there as a postdoc after receiving his MIT Ph.D.

RIXS, with its specific sensitivity to the excitons from the nickel atoms, allowed the team to “set the basis for a general framework for nickel dihalide systems,” says Pelliciari. “it allowed us to directly measure the propagation of excitons.”

Comin’s colleagues on the work include Connor A. Occhialini, an MIT graduate student in physics, and Yi Tseng, a recent MIT postdoc now at Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY). The two are co-first authors of the Physical Review X paper. Additional authors are Hebatalla Elnaggar of the Sorbonne; Qian Song, a graduate student in MIT’s Department of Physics; Mark Blei and Seth Ariel Tongay of Arizona State University; Frank M. F. de Groot of Utrecht University; and Valentina Bisogni and Jonathan Pelliciari of Brookhaven National Laboratory.

More information:

Connor A. Occhialini et al, Nature of Excitons and Their Ligand-Mediated Delocalization in Nickel Dihalide Charge-Transfer Insulators, Physical Review X (2024). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevX.14.031007

Provided by

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Citation:

Physicists report new insights into exotic particles key to magnetism (2024, August 1)

retrieved 1 August 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-08-physicists-insights-exotic-particles-key.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.